The Hits

Prologue: Decline of the Communal element

“Hollywood really became entrenched across society and in all sorts of different ways that went way beyond just going to the cinema or to be entertained. And that effect is still felt today. But of course the way the films were seen by Caribbean audiences was very particularly Caribbean. There was a tradition of interacting with the cinema that was being seen, talking back to the screen, people commenting in the cinemas, particularly down in the pit as it was known as, the cheap seats as opposed to the more expensive seats in the balcony. All that’s gone now, there are the multiplexes now for those who still go to the cinema and you know, the tradition of talking back to the screen has all but disappeared. It was a way of Caribbean people inserting themselves into the drama and making themselves part of what they were witnessing. I have to say I don’t know to what extent that tradition extended to the diaspora. For example, when Caribbean audiences saw The Harder They Come in cinemas in London in the 1970s, how did they respond? Were they reacting to the film the way audiences in Kingston were reacting? It’s a good question, but just to say that the rich tradition is all but gone now. It’s also because cinema viewing habits have changed. We don’t go to the cinema as we used to.”

– Ali, Jonathan (2022). An interview with Lisa Harewood and Jonathan Ali, The Twelve30 Collective. Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies. Vol. 19, Issue. By Hanna Klien-Thomas of Oxford Brookes University, UK. Retrieved at https://www.participations.org/19-01-16-klien-thomas

A Retrospective on Caribbean Cinema

Written by: WI of The Future Staff

Date: June 2nd, 2025

INTRODUCTION: A Fractured Lineage: Post-Colonial Identity Crisis

Violence. Black & Brown Men in masculine drapes. And a rage fueled by earnest dreams & a sad past & present – set against a reggae/dancehall infused track list.

Which iconic feature of Caribbean cinema could we be referring to, here? With knowledge of this region’s cinematic catalogue, your list of best guesses may go:

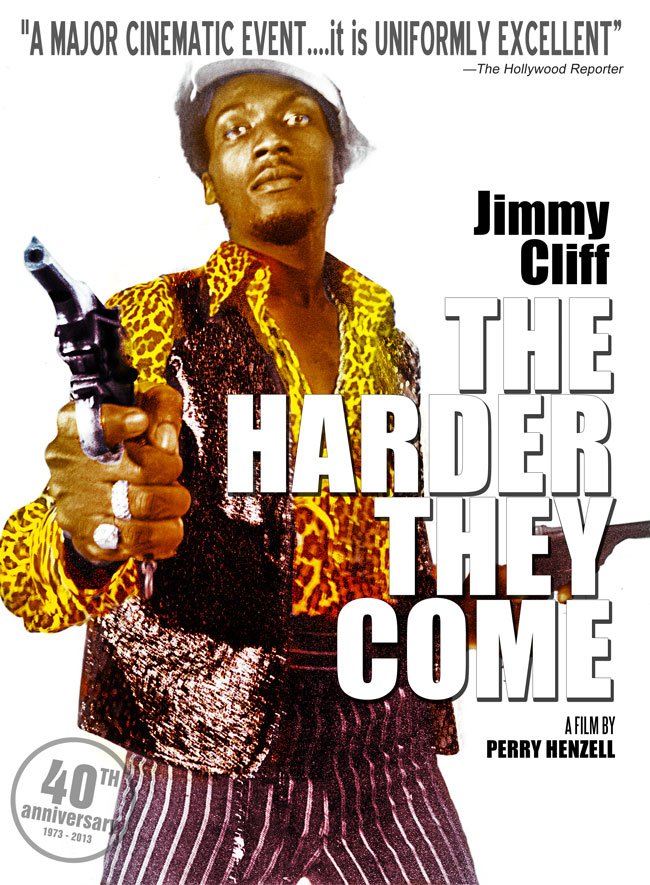

The Harder They Come

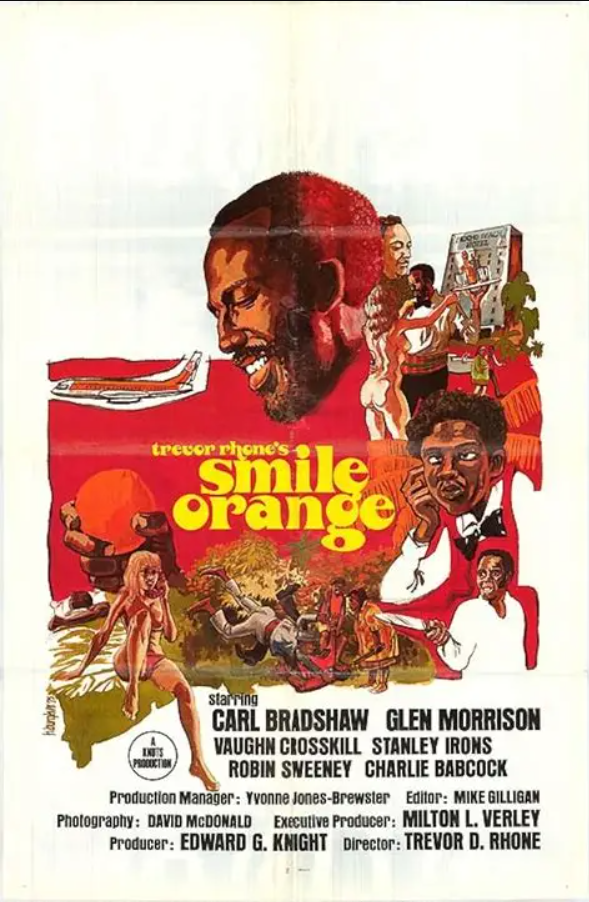

Smile Orange

Bim

The crux of this article is our belief that Caribbean cinema, despite its roots & promising beginnings dating back to the 1970s, has yet to intervene in the global conversation on film; its identity too nebulous to make it even considered as being at the margins of global film discourse. For a region of such rich cultural foundation and socially charged narratives, why is it that years down the line we’ve yet to see its evolution into more sophisticated forms and themes of storytelling?

THE RHETORIC: What would happen if we stop importing, would cinema die in the Caribbean?

The Influence of BrandinG

For a small enterprise Caribbean cinema loves its tropes:

‘GHETTO’ CINEMA & Macho Men

The struggling man from an underdeveloped neighborhood, escaping poverty through a hustle that leads to a moral impasse – ultimately ending in crime or addiction, and resulting in the estrangement from loved ones, particularly the female lead (usually a designated love interest).

Does this sound familiar?

The Sociopolitical Collapse

Usually a documentary, set in the post-independence period of a nation, that represents the heavy price of freedom and leadership.

We’re speaking here about the Cuban masterpiece Memories of Underdevelopment (1968) – ranked as one of the best films of all time by the Sight & Sound magazine’s 2012 poll – as well as the lesser known, but powerful Trinidadian documentary 70: Remembering a Revolution (2011).

The Intercultural Family Drama

This is the Starcrossed Lovers (à la Romeo and Juliet) trope with the added caveat of inter-cultural tensions and blatant racism or prejudice, typically showcasing the ethnic forbidden crossings of the Afro-Indo populace.

Refer to:

Bazodee

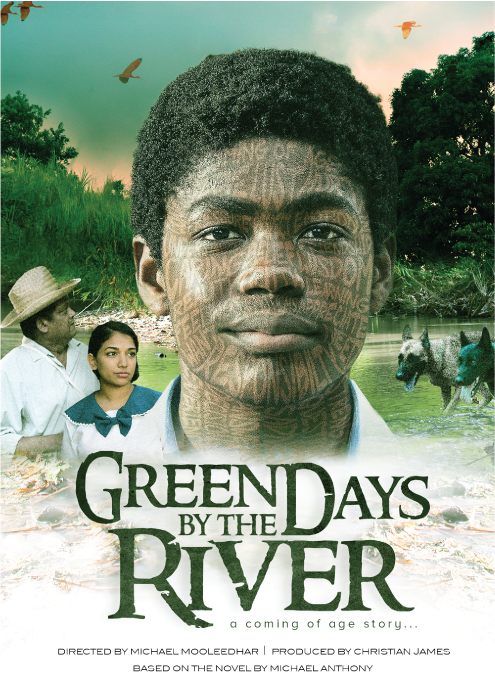

Green Days By The River

Moko Jumbie

Nonetheless, we wonder whether these tropes reduce Caribbean storytelling to stereotypes that reflect an outdated perspective on the region…

CONTEMPORARY CINEMA: Art and Imitation

The brand of Caribbean cinema has not changed much since its birth. It’s still nascent and hasn’t been able to germinate into complex media and storytelling. Latest cinematic entries like Sacrificial (2024) steal elements from western media like Taken (2008), or The A-Team. But the failure of these entries to become more of the sum of their parts begs the question: if we are going to take material from abroad, how do we digest this material and make it ours?

Let’s look at how we once successfully did this:

Caribbean Realism

Did Caribbean cinema hit its peak in the 1970s?

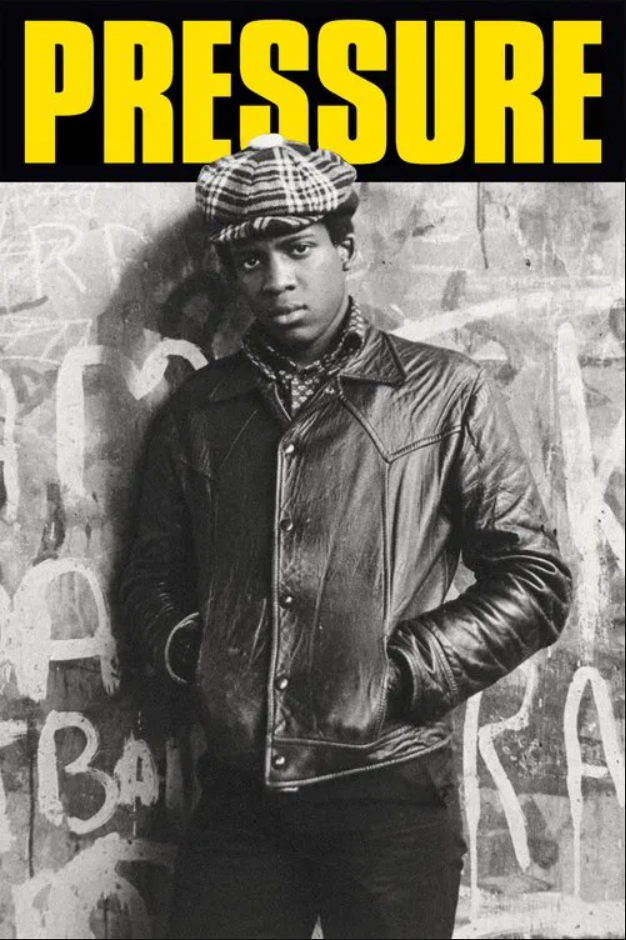

That decade saw iconic films like The Harder They Come (1972) and Pressure (1976)address socio-political turmoil, violence and resistance to dominant power structures. Perhaps inspired by the gangster films of Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola, as well as the spaghetti westerns of the 1950s, these films are decidedly masculine in orientation, and express the protagonists’ desire to escape from a claustrophobic, highly violent environment. But what distinguishes these films from present day cinema is their lyricism. Pressure, for instance, shows the violent yoke of acculturation and migration through its manipulation of sound as which mirrors the immigrants’ negotiation between inside and outside or the cultural mixture that leads to conflicts within their space. The lyrical motif, “out of my mother’s belly/into a world so unfriendly” reverberates throughout the film, echoing the pain of transition from one’s “motherland” into London.

We can also observe a similarity between Caribbean cinema and Bollywood cinema in its representation of masculinity. Isn’t Bim’s (1974) eponymous hero,after all,similar to the characters played on screen by Amitabh Bachan, “The Angry Young Man of Bollywood?”

But being the first to break ground often means that its imitators fall short. The narrative gets replicated in consequent Caribbean feature films, in what becomes an endless reiteration of the formula that sees the downfall of the lead, mirrored by strained or broken romantic relationships. This realist and archetypal male narrative—“the struggling man from the ghetto”—has become a shorthand for Caribbean neorealism. These films are meant to hold a mirror up to a broken society, but what if the mirror itself has been cracked, its shards reflecting, over and over, the same distorted image?

So far, Caribbean cinema seems to be a relic of hyper-masculinity, poverty, folklore, and resistance. These are the elements that have characterized Caribbean cinema since its birth, elements still in focus today, like a stamp we wear in testament to the past – where we are too sentimental to its meaning that it’s become our brand.

A Diverging Trend: Folklore in Caribbean Cinema

Western media has its vampires, demons, werewolves (have a look at our Nosferatu/Sinners review!) – creatures that carry a symbolic potency exploited by filmmakers who find something new to say about these myths.

On the other hand, Caribbean cinema appears to be stuck. Folklore is diverging and promising section of storytelling in the Caribbean and yet its representation on screen has been feeble. Moko Jumbie (2017) represents one of the most recent entries into this genre, xxx [GU1] [GU2]

Nonetheless we cherry-pick the markers of our culture, yet how much do we plumb the depths of these markers? Caribbean folklore on screen often feels superficial, dehistoricized, and decontextualised. Rather than invested with any real profundity, the folklore figures are emptied of their historical meanings, and consigned as figures who inspire shallow emotions of horror and shock. Octavio Paz, in his book of essays The Labyrinth of Solitude writes that a culture’s return to its mythical past is a way of charting its future. Delving into the historicity of our myths is a journey that is yet to be undertaken and exploited by filmmakers.

This is of course linked to one of Caribbean cinema’s major obstacles: its reliance on imported story formulas. Films such as Green Days by the River (2017) show the potential of adaptation from local literature, but such instances are rare. The scarcity of writers and original screenplays contributes to a cinema that mimics more than it creates.

Caribbean cinema once mirrored movements like British kitchen-sink realism and 1970s American crime dramas, reflecting a revolutionary spirit in a time of socio-political upheaval. Films such as Bim, Smile Orange, and The Harder They Come embodied this raw energy. But where is the Evolution?

Lack of Infrastructure

The Decline of the Communal Element: The Ghost of Cinema Past, Present & Future

Post-1970s, the cinematic output has waned. The communal cinema culture—talking back to the screen, claiming a space in the narrative—has disappeared with the rise of gentrified multiplexes. What was once an interactive experience has become passive, and with it, a sense of ownership and participation in Caribbean storytelling has faded.

To imagine the future of a cinematic landscape that currently pulsates between the niche and nonexistent we must reexamine the past and take accountability for this liminal existence.

Margins of the Margins – Material Limitations

The Global Market

The politics of the West Indian world was vastly more interesting in the 70s, creating its own intrigue that could be exploited on screen and in a global market as films like Pressure showed. The Caribbean in recent years would have no choice but to default to the indie world.

But, even within the independent film world, Caribbean cinema is often overlooked.

Filmmakers Lisa Harewood and Jonathan Ali, of the Twelve30 Collective, speculate, for instance, that the complexity and diversity of Caribbean stories make these films hard to market in a global system driven by easily marketable archetypes.

This viewpoint seeks to put Caribbean cinema in a vacuum, with the implication that our alienation seems to be a symptom of our culture and geographical location.

As time passes the validity of this observation, however, may be relevant to regional filmmakers. Cinema as a theme park vs Cinema of substance being the new age divide; where Caribbean cinema arguably had a better foothold when film preferred voyeurism over spectacle.

But how is this complexity and diversity represented? Is it inherent in the works or something we forcibly inject? How do we represent our culture and still be globally marketable?

Filmmakers like Taika Waititi have tried to solve this dilemma. In his films culture breathes beneath the archetypes of ‘marketable cinema’. In Jojo Rabbit (2019), What We Do in The Shadows (2014) diversity surfaces just enough to be recognized, but never made into a caricature. On the material side, filmmakers like Peter Jackson who breach the mainstream pay credit to their homelands in their films. The Lord of the Rings trilogy was notably shot in New Zealand, where the hobbit houses attract tourists to this day.

Indigenous filmmaking remains in the shadows of the Americas.

Indigenous Caribbean filmmaking is more limited than diasporic filmmaking in that our market is obviously microscopic in comparison. Moreover, our smaller market self-sabotages through its projection of the outside vs inside mental debacle, such that our self-representation assumes a culturalized, pro-American stigma. The world beyond our shores where the grass being greener; we will often gravitate to the cinema of the larger world. Cinema has always been voyeurism and voyeurism is an escape. Internal cinema is not necessarily compatible with voyeurism, probably because its realism hits a little too close to home. These themes are also reflected in the films themselves; the need for an escape.

A Cinema of Resentment

One significant trend in Caribbean cinema is the representation of home being somewhere to escape from – which arguably mirrors filmmakers’ attitudes towards the Caribbean. Doubles (2022) for example is arguably a film that seeks to explain migration out of the Caribbean. She Paradise (2020) on the other hand is a coming-of-age story that ends on a cynical note. Both films seem to gesture towards a harsh realism that recalls the 1970s cinema that saw its protagonists try and fail to escape. But intermixed in these two recent features is a love for the Caribbean’s beauty (whether in food, or dance) that complicates the desire to escape.

These complicated emotions signify that Caribbean cinema, too, is coming of age. This also translates materially. Caribbean Cinema is trying to reconcile the lack of material support with the desire to represent itself, and its beauties.

The Linguistic Divide

The Anglophone Caribbean rarely intersects with the Spanish- or French-speaking film outputs of the region, resulting in a fractured cinematic identity.

And because of the preponderance of American and British media, it’s harder for films from the anglophone Caribbean to access these linguistic markets as compared to Spanish and French speaking Caribbean cinema. This is because Spanish and French Caribbean have access to larger linguistic markets (Latin America, Europe, Africa): spaces where cinema can still thrive. Anglo-American media in particular dominates the sector, with a million-dollar box offices where the Anglo-Caribbean lack the promotional and developmental power to break through.

French and Spanish Caribbean Cinema often flourish their culture, even when inspired by Western cinema. They took what works for other cultures and assimilated it into their specific cultural experience.

Where to?

The future of Caribbean cinema may lie in striking a balance between its folkloric past and a new narrative realism that is both socially relevant and mythically potent. Like Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives or Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth (inspired in part by the Spanish masterpiece The Spirit of the Beehive) Caribbean film must find ways to blend memory, myth, and modernity in poetically unique ways.

What Caribbean cinema needs is not only funding or exposure but daring writers—those who can develop new futures without discarding the past. Until then, we continue to reproduce the same tired stories and themes on the screen.

Preservation is inimical to growth.

More than this, we need more critical pieces. The industry infrastructure requires critical voices to show that people are engaged. Inhibiting criticism coddles the industry. It inhibits a conceptualization of what can be considered ‘good art’ in the Caribbean. What are our standards for good art? Are we again importing from abroad what can be considered as good art? Or are we constructing our own terms of criticism? We simply would not know unless we critique what we have, inspire others to engage with the criticism, and see what can be churned out. This is why statements like ‘Trini to the World’ need to be grounded in realistic expectations that can confront our fear of not measuring up to international standards. Before we can export our films and creative work, we must first develop a clearer understanding of what success looks like on our own terms, rather than chasing validation from external markets.

References / Suggested Viewing

Further Reading